Executive Summary

For the first time, more than half of the world’s population are covered by some form of social protection. While this is welcome progress, the unvarnished reality is that 3.8 billion people are still entirely unprotected. The pressing need to make the human right to social security a reality for all is rendered even more urgent given the role social protection must play in addressing an even more substantial challenge: that is, the need for climate action and a just transition to address the triple planetary crisis – climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss – that imperils our world. With major tipping points on the verge of being crossed due to warming right now, the climate crisis represents the singular gravest threat to social justice.

A rapid move to a just transition is therefore urgently required as a response. Universal social protection systems have an important role to play to help realize climate ambitions and facilitate a just transition. With an especially sharp focus on the climate crisis and the exigency of a just transition, this report provides a global overview of progress made around the world since 2015 in extending social protection and building rights-based social protection systems. In doing so, it makes an essential contribution to the monitoring framework of the 2030 Agenda.1 And it calls on policymakers, social partners and other stakeholders to accelerate their efforts to simultaneously close protection gaps and realize climate ambitions.

Five messages emerge from this report.

Social protection makes an important contribution to both climate change adaptation and mitigation . Social protection is fundamental for climate change adaptation2 as it tackles the root causes of vulnerability by preventing poverty and social exclusion and reducing inequality. It enhances people’s capacity to cope with climate-related shocks ex ante by providing an income floor and access to healthcare. It also contributes to raising adaptive capacities, including those of future generations through its positive impacts on human development, productive investment, and livelihood diversification.

Moreover, an inclusive and efficient loss and damage response at scale can leverage social protection systems, particularly when high levels of coverage and preparedness exist. Social protection systems are also key for compensating and cushioning people and enterprises from the potential adverse impacts of mitigation3 and other environmental policies. When combined with active labour market policies, they can help people transition to greener jobs and more sustainable economic practices. Social protection can also directly support mitigation efforts. The greening of public pension funds, the progressive conversion of fossil fuel subsidies into social protection benefits, and the provision of income support to disincentivize harmful activity to protect and restore crucial natural carbon sinks, are some of the options to support emission reductions.

Social protection is therefore an enabler of climate action and a catalyst for a just transition and greater social justice. Social protection systems, as part of an integrated policy response, meet the imperatives of mitigation and adaptation in an equitable manner. Social protection helps to protect people’s incomes, health and jobs, as well as enterprises, from climate shocks and the adverse impacts of climate policies. Social protection encourages productive risk-taking and forward planning and thus can ensure that everyone – including the most vulnerable – can gain from climate change adaptation measures. It can enable job restructuring, protect living standards, maintain social cohesion, reduce vulnerability, and contribute to building fairer, more inclusive societies, and sustainable and productive economies. However, social protection cannot do this on its own. It needs to work in tandem with other policies to enable effective mitigation and adaptation policies, which are so utterly vital for a liveable planet.

Decisive policy action is required to strengthen social protection systems and adapt them to new realities, especially in the countries and territories most vulnerable to climate change, where coverage is the lowest. Social protection

increases the resilience of people, economies and societies by providing a systematic policy response to mutually reinforcing life-cycle risks and climate-related risks (which look poised to become increasingly inseparable and indistinct with each decimal point of global warming). In this context, policymakers will have to achieve a double objective: implementing climate policies to support mitigation and adaptation efforts to contain the climate crisis, while at the same time strengthening social protection to address both ordinary life-cycle risks and climate risks. In the context of an evolving risk landscape, policymakers must ensure their social protection systems can deal with both types of risk.

However, the capacity of social protection systems to contribute to a just transition is held back by persistent gaps in social protection coverage, adequacy and financing. These hinder the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Investing in reinforcing social protection systems is indispensable for a successful just transition. The costs of inaction are enormous, and it would be irrational and imprudent not to invest. The case for strengthening social protection systems is therefore as compelling as it is urgent. Without investment in universal protection systems, the climate crisis will exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, poverty and inequalities, when precisely the opposite is needed. Moreover, for ambitious mitigation and environmental policies to be feasible, social protection will be needed to garner public support. Human rights instruments and international social security standards provide essential guidance for building universal social protection systems capable of responding to these challenges and realizing the human right to social security for all.

Social justice must inform climate action and a just transition, with human rights at the heart of the process. Social protection can help ensure no one is left behind. It can contribute to rectifying long-standing global and domestic inequalities and inequities rendered more pronounced by the climate crisis. The climate crisis can only be overcome through common effort but with differentiated responsibility proportional to capacity. It needs to be recognized that special remedial responsibility lies with those primarily responsible for the crisis. This has major implications for financing social protection at the domestic level, and for the role of international financial support for countries with insufficient economic and fiscal capacities that have contributed least to the crisis but are bearing its brunt. This constitutes a key element of social justice.

.Progress, yes, but billions are left languishing and unprepared for the life-cycle and climate shocks ahead

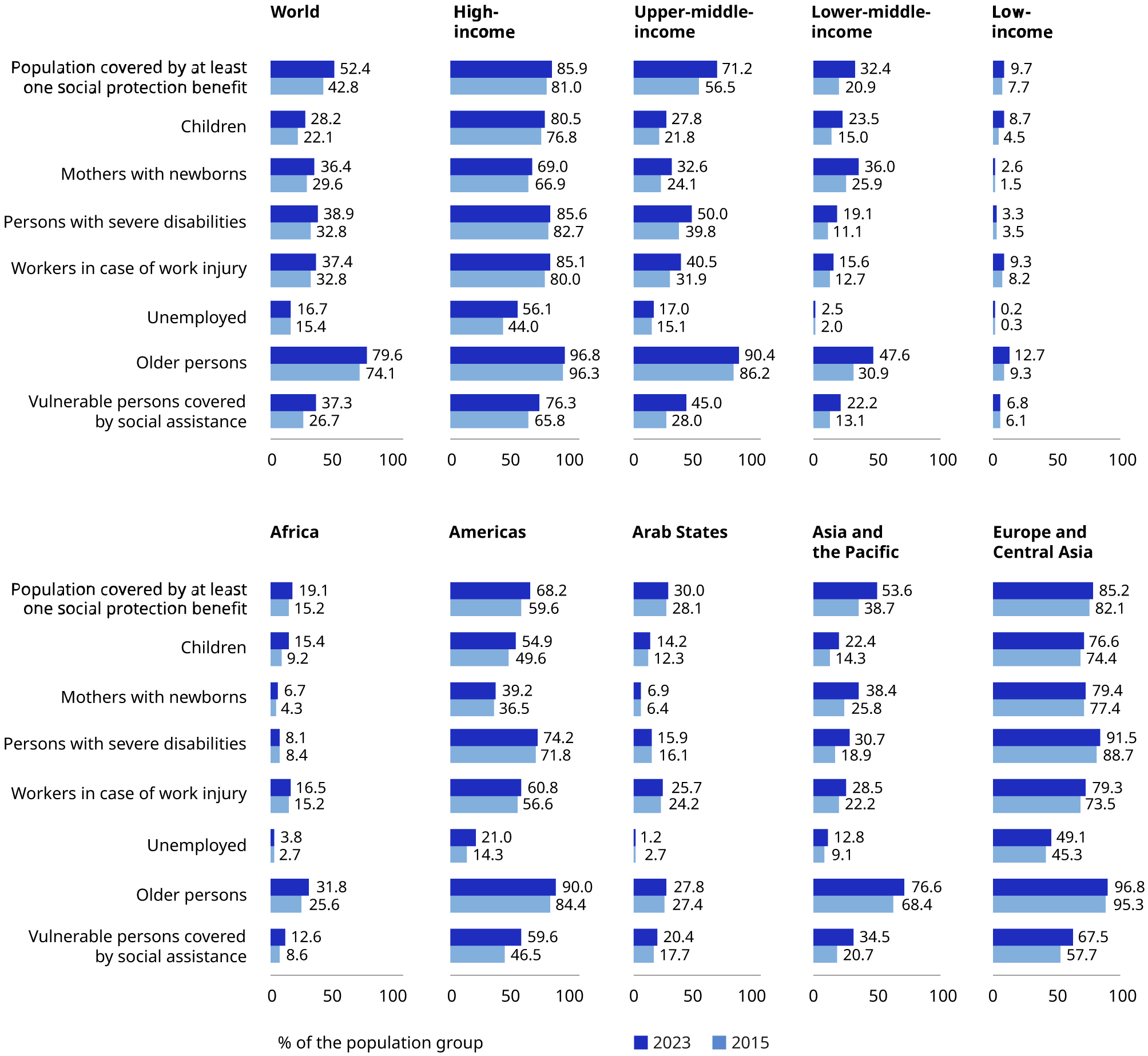

Since the last edition of the World Social Protection Report, social protection coverage has surpassed an important milestone globally. For the first time, more than half of the world’s population (52.4 per cent) are covered by at least one social protection benefit (SDG indicator 1.3.1), increasing from 42.8 per cent in 2015 (see figure ES.1). This is welcome progress.

If progress were to continue at this rate at the global level, it would take another 49 years – until 2073 – for everyone to be covered by at least one social protection benefit. This pace to close protection gaps is too slow.

Moreover, the world is currently on two very different and divergent social protection trajectories: high-income countries (85.9 per cent) are edging closer to enjoying universal coverage; and upper-middle-income countries (71.2 per cent) and lower-middle-income countries (32.4 per cent) are making large strides in closing protection gaps. At the same time, low-income countries’ coverage rates (9.7 per cent) have hardly increased since 2015, which are unacceptably low.

Gender gaps in global legal and effective coverage remain substantial. Women’s effective coverage, for at least one social protection benefit, lags behind men’s (50.1 and 54.6 per cent, respectively). For comprehensive legal coverage, a similar inequality is observed. Only 33.8 per cent of the working-age population are legally covered by comprehensive social security systems. However, when this figure is disaggregated, it reveals a pronounced gender gap, with a coverage rate of 39.3 per cent for men and 28.2 per cent for women – an 11.1 percentage point difference. Social protection systems must become more gender-responsive as part of a larger set of policies to address inequalities in labour markets, employment and society.

Figure ES.1. SDG indicator 1.3.1: Effective social protection coverage, global, regional and income-level estimates, by population group, 2015 and 2023 (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional and income-level aggregates are weighted by population. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024;

For people not covered through social insurance, it is important to note that, in its absence, social assistance or other non-contributory cash benefits play an essential role in ensuring at least a basic level of social security. Globally, coverage has increased from 26.7 per cent to 37.3 per cent of vulnerable persons since 2015. This increase is explained, in part, by the temporary policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, higher coverage may also stem from increased needs due to increasing poverty, vulnerability and decent work deficits. Irrespective of the explanation, greater efforts are needed to facilitate transitions from social assistance into decent employment (including self-employment) covered by social insurance, which provides higher levels of protection and relieves pressure on government budgets.

.A daunting prospect: Countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis are woefully ill-prepared

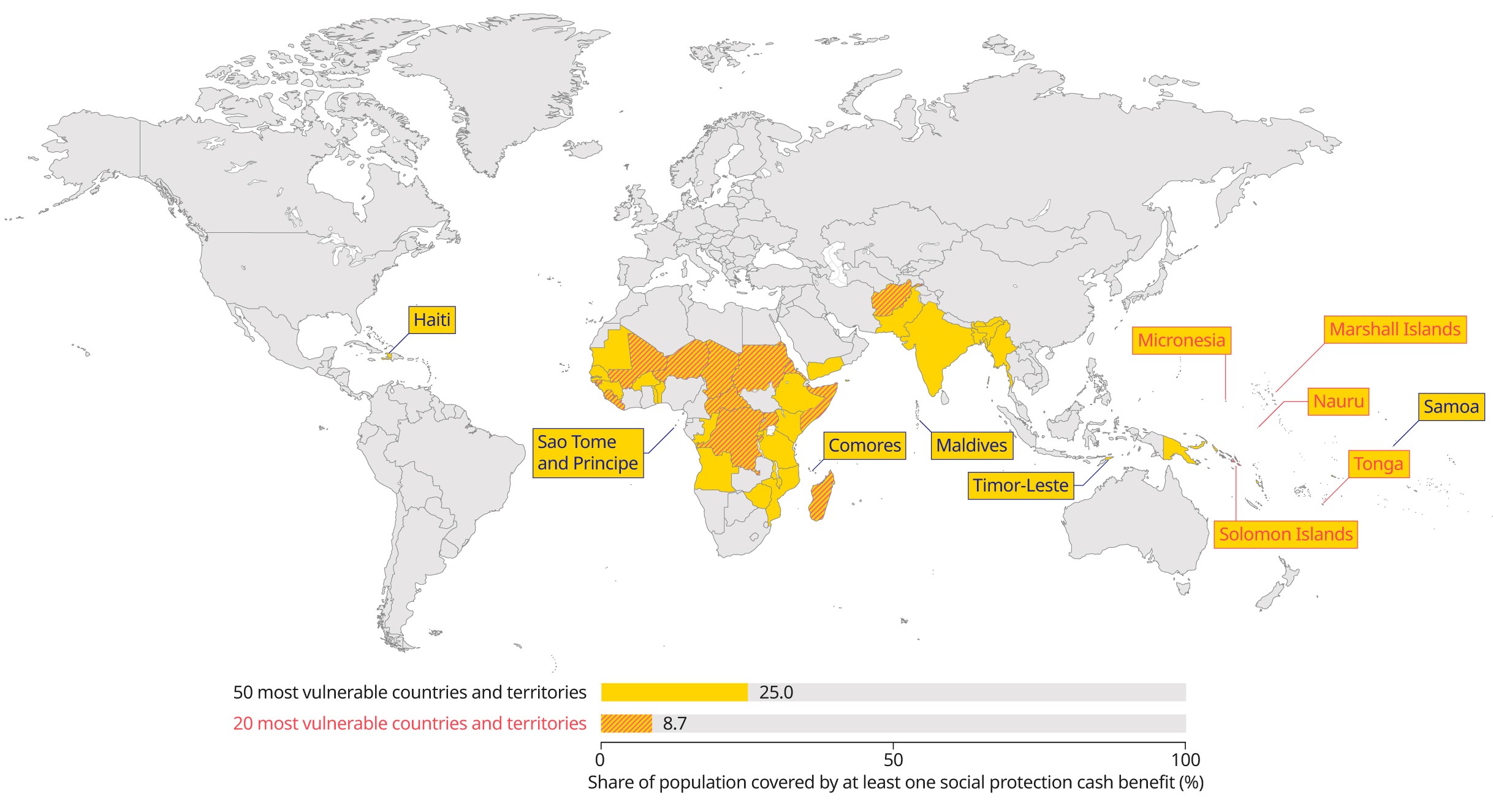

Populations in countries at the frontline of the climate crisis and most susceptible to climate hazards remain woefully unprepared. In the 20 countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis, just a mere 8.7 per cent of the population is covered by some form of social protection, leaving 364 million people wholly unprotected (figure ES.2). And some 25 per cent of the population in the 50 most climate-vulnerable countries are effectively covered. For the latter, this translates to 2.1 billion people currently facing the ravages of climate breakdown with no protection, relying on their own wits and kin to cope.

Figure ES.2. The 20 and 50 countries most vulnerable to climate change and their weighted average effective coverage by at least one social protection cash benefit, 2023 (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population. Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO.

Sources: ILO estimates,

This is no way to proceed in the context of a more volatile climate future. And the abject plight of these people is made even bleaker by the large financing gap that impedes having at least a social protection floor. The annual financing gap in the 20 most vulnerable countries equates to US$200.1 billion (equivalent to 69.1 per cent of their GDP) and, in the 50 most vulnerable, it is US$644 billion (equivalent to 10.5 per cent of their GDP). Filling these financing gaps is not insurmountable if domestic capacities are built up, but this will require concerted international support, especially in the most vulnerable countries.

.Protection gaps are largely associated with significant underinvestment in social protection

Financing gaps in social protection are still large. To guarantee at least a basic level of social security through a social protection floor, low- and middle-income countries require an additional US$1.4 trillion or 3.3 per cent of the aggregate GDP (2024) of these countries per annum, composed by 2.0 per cent of GDP or US$833.4 billion for essential health care and 1.3 per cent of GDP or US$552.3 billion for five social protection cash benefits. More specifically, low-income countries would need to invest an additional US$308.5 billion per year, equivalent to 52.3 per cent of their GDP, which is unfeasible in the short term without international support.

Ambitions to close gaps in the coverage, comprehensiveness and adequacy of social protection systems are stymied by significant underinvestment in social protection. On average, countries spend 12.9 per cent of their GDP on social protection (excluding health), but this figure masks staggering variations between countries. High-income countries spend 16.2 per cent; upper-middle-income countries, 8.5 per cent; lower-middle-income countries, only 4.2 per cent; and low-income countries, a paltry 0.8 per cent.

Increasing the adequacy of social protection is paramount too. Persistent adequacy gaps inhibit the potential of social protection to prevent and reduce poverty, and enable a dignified life. Ensuring adequate benefits across people’s lives is key to guaranteeing a social protection floor and striving towards higher benefit levels. The climate crisis will most likely lead to increased needs, including due to higher prices, which will require a commensurable increase in public expectations for adequate benefits.

For social protection systems to fulfil their potential in addressing life-cycle risks and responding to climate change, they must be further reinforced. Additional efforts are therefore needed to ensure universal, comprehensive and adequate protection, while ensuring that social protection systems are equitably and sustainably financed. The cost of inaction on investing in social protection is enormous, comprising lost productivity and prosperity, heightened social cohesion risks, squandered human capabilities, unnecessary pain, morbidity and early death and many more socio-economic negativities.

.Social protection continues to be elusive for 1.8 billion children

Highlights

Social protection remains elusive for the vast majority of children. For children aged 0 to 18 globally, 23.9 per cent receive a family or child benefit, meaning 1.8 billion children are not.covered. For children aged 0 to 15, 28.2 per cent of children are covered, up by 6.1 percentage points since 2015. This equates to 1.4 billion children missing out.

Fewer than one in ten (7.6 per cent) children aged 0 to 18 in low-income countries receive a child or family cash benefit, leaving millions vulnerable to missed education, poor nutrition, poverty and inequality, and exposing them to long-lasting impacts. Children, especially those in poverty, are bearing the brunt of the climate crisis.

The climate crisis has been described as structural violence against children, which compromises their well-being and prospects. This underscores the importance of making social protection systems more inclusive and resilient so that they continue to achieve their core objectives and support children’s additional needs due to climate change.

Public expenditure on social protection for children needs to increase. On average, 0.7 per cent of GDP is spent on child benefits globally. Again, large regional disparities exist; the proportion ranging from 0.2 per cent in low- income countries to 1.0 per cent in high-income countries.

.Pronounced protection gaps remain for persons of working age

Highlights

Global coverage trends between 2015 and 2023 (including SDG indicator 1.3.1) show some, yet still insufficient, progress for persons of working age, leaving many millions unprotected or inadequately protected. These protection gaps will be further aggravated by climate hazards and climate mitigation and adaptation policies.

Maternity protection: 36.4 per cent of women with newborns worldwide receive a cash maternity benefit, up by 6.8 percentage points. This equates to 85 million women with newborns not covered. In addition, inequalities in access to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health persist and exposure to climate change hazards has consequences for maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Sickness benefits (legal coverage): 56.1 per cent of the labour force in the world, representing

34.4 per cent of the working-age population, is legally entitled to sickness benefits. This means 4.1 billion working-age persons are not legally protected. Even when covered, limited adequacy, duration and eligibility criteria may create protection gaps. Climate change creates new challenges for productivity and sickness protection owing to the spread of existing and new diseases.

Employment injury protection: 37.4 per cent of workers enjoy employment injury protection for work-related injuries and occupational disease, up by 4.6 percentage points. This leaves 2.3 billion workers totally uncovered. Adverse labour market structures and weak enforcement of schemes, especially in lower- income countries, perpetuate these gaps. Climate hazards like extreme heat will increase employment injury risks, and occupational safety and health needs.

Disability benefits: 38.9 per cent of people with severe disabilities receive a disability benefit, up by 6.1 percentage points. This results in 146 million persons with severe disability not covered. The additional services which persons with disabilities need are often insufficient to meet their diverse needs. Climate change further increases the vulnerability of persons with disabilities.

Unemployment protection: 16.7 per cent of unemployed people receive unemployment cash benefits, up by 1.3 percentage points. This translates to 157 million unemployed persons not being covered. Youth, self-employed workers, workers on digital platforms, agricultural and migrant workers often lack unemployment protection. And many existing schemes are not prepared to tackle climate-related challenges nor facilitate the decarbonization of carbon-intensive sectors.

Expenditure estimates show that, worldwide, 4.8 per cent of GDP is allocated to non-health public social protection expenditure for people of working age. To a large extent, limited expenditure explains protection gaps for working-age persons.

.Older persons still face coverage and adequacy challenges

Highlights

Pensions are the most prevalent form of social protection globally. Worldwide, 79.6 per cent of people above retirement age receive a pension, up by 5.5 percentage points since 2015. Nonetheless, more than 165 million individuals above the statutory retirement age do not receive a pension.

Ensuring adequate protection in old age remains a challenge, particularly for women, workers with low earnings, those engaged in precarious employment, workers on digital platforms, and migrant workers. These challenges are likely to be exacerbated by climate change, in the form of involuntary migration, fragmented careers or general climate-induced economic pressure.

In many countries, especially those with widespread informal employment, the expansion of coverage of contributory pensions has not been fast enough to guarantee adequate income security in old age. The introduction of tax-financed pensions provides an important source of income for older persons with insufficient entitlements to contributory pensions. Yet, in some countries, benefit levels are insufficient to guarantee a social protection floor for older persons.

Globally, public expenditure on pensions and other non-health benefits for older people averages 7.6 per cent of GDP. However, substantial regional variations still exist, with expenditure levels ranging from 10.5 per cent of GDP in Europe and Central Asia to 1.7 per cent in Africa.

The climate crisis threatens the financial sustainability and adequacy of pension schemes. Consequently, pension schemes must adapt to contend with climate-related risks to ensure long-term sustainability and protect the quality of life of beneficiaries. Pension funds can also help combat the climate crisis through strategic investment in sustainable and low-carbon assets.

.Social health protection: an essential contribution to universal health coverage

Highlights

The right to social health protection is not yet a universal reality. While more than four fifths (83.7 per cent) of the global population is covered by law, only 60.1 per cent of the global population are effectively protected by a health protection scheme. This means 3.3 billion people do not enjoy protection. Coverage has stalled since 2020, showing important implementation gaps. In addition to extending health protection, investing in the availability of quality healthcare services is crucial.

Barriers to healthcare access remain in the form of out-of-pocket health expenditure incurred by households, physical distance, limitations in the range, quality and acceptability of health services, long waiting times linked to shortages and unequal distribution of health and care workers, and opportunity costs such as lost working time and earnings.

Out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare is increasing globally and pushed 1.3 billion people into poverty in 2019. Collective financing, broad risk pooling and rights-based entitlements are key conditions to support effective healthcare access for all in a shock- responsive manner.

Stronger linkages and better coordination between access to healthcare and income security are urgently needed to address key determinants of health. The climate crisis is directly impacting people’s health, while also exacerbating existing socio- economic inequalities, which act as powerful determinants of health equity. Health and well- being should not be the privilege of the few, and the inequalities triggered by the climate crisis call for urgent investment.

.Time to up the ante: Towards a greener, economically secure and socially just future

Time is quickly running out for arresting runaway global heating and achieving universal social protection, with less than six years remaining to the key milestone of 2030. It is time to up the ante, accelerate progress in social protection and make a just transition. This is essential for current and future generations. It requires significant investment, determination and political will from both national policymakers and international actors. Safeguarding the planet – while also protecting people’s health, incomes, jobs and livelihoods, as well as enterprises – and maintaining a liveable planet should provide ample impetus for policymakers to build social protection systems. To this end, several priorities can be identified:

Mitigating the climate crisis and achieving a just transition requires giving sufficient attention to building rights-based universal social protection systems. Countries must intensify their efforts to address the existential threat of the climate crisis. Social protection is among the most powerful policy tools that governments can deploy to manage this challenge fairly by ensuring that everyone is adequately protected. This must be part of an integrated policy response. This can help secure the political legitimacy of climate policies. Rectifying inequities intrinsic in the climate crisis demands global justice, including solidarity in financing.

By reinforcing social protection systems, States can demonstrate that they intend to protect their people through a reinvigorated social contract. This is essential for promoting well-being, social cohesion and the pursuit of social justice. Strong social protection fosters state-society trust, can guarantee that all members of society are well protected, and engenders a willingness to go along with climate policies.

Keeping alive the promise of leaving no one behind remains paramount. This means a) pivoting from reducing poverty to preventing poverty and moving away from flimsy social safety nets towards solid social protection floors, and progressively reaching higher, more adequate levels of protection; b) ensuring that social protection systems are gender- responsive; c) facilitating access to quality care and other services; d) making health and well- being a more central focus of our economies.

Preparedness for climate shocks and just transition policies requires comprehensive social protection systems to be in place ex ante. This means getting the basics right and formulating and implementing national social protection strategies and policies through social dialogue now rather than later. Systems can contribute to preventing, containing and softening the impacts of crises, promoting swift recovery and building people’s capacity to cope with shocks as well as everyday risks. In humanitarian crises, this requires working across the humanitarian- development- peace nexus, using existing health and social protection systems to the extent possible, and systematically reinforcing them.

Further investment is essential to achieve universal and robust social protection systems. Domestic resource mobilization is critically important for addressing both life-cycle and climate risks in a sustainable and equitable way. Countries with limited fiscal capacities, many of which are also highly vulnerable to the climate crisis, need international financial support to enable them to fill financing gaps and build their social protection systems.

There are enormous gains to be had if universal social protection is accorded its due policy priority in climate action and a just transition. As part of an integrated policy framework, social protection can ensure that everyone can reap the benefits of a new greener prosperity, a reinvigorated social contract and a rejuvenated planet more hospitable to life and future generations. The opportunity is there if policymakers want to take it.

1 Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Reports due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

2 Climate change adaptation refers to the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate change and its effects in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities.

3 Climate change mitigation refers to actions that reduce the rate of climate change (for example, keeping fossil fuels in the ground) or enhancing and protecting the sinks of greenhouse gases that reduce their presence in the atmosphere (for example, forests, soils and oceans).